Tracking SARS-CoV-2 evolution during persistent cases provides insight into the origins of Omicron and other global variants. What can scientists do with this knowledge?

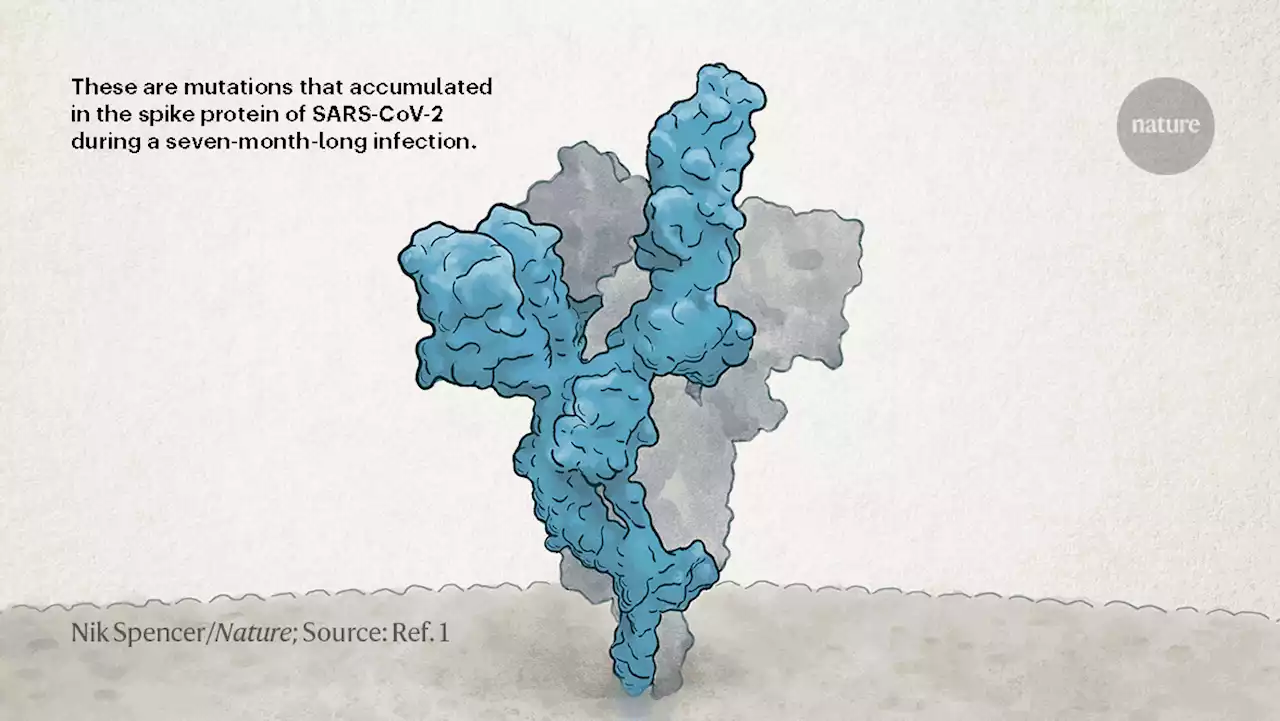

These are mutations that accumulated in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 during a seven-month-long infection.Virologist Sissy Sonnleitner tracks nearly every COVID-19 case in Austria’s rugged eastern Tyrol region. So, when one woman there kept testing positive for months on end, Sonnleitner was determined to work out what was going on.

. “When Omicron was found, we had a great moment of surprise,” Sonnleitner says. “We already had those mutations in our variant.”Omicron did not arise from the woman’s infection, which doesn’t seem to have spread to anyone. And although no definitive links have been made to individual cases, chronic infections such as hers are a leading candidate for thethat have driven COVID-19 surges globally.

In acute SARS-CoV-2 infections, which generally last a week or two before being cleared by the immune system, versions of the virus with advantageous mutations have little time to outcompete those that lack them. The odds of a virus with such an advantage being transmitted to another individual are therefore small. Studies suggest that only a few virus particles — maybe even just one — are needed to seed a new infection.

As a result of chronic infections, globally, “this virus has opportunities not just to evolve in one way, in one direction, but literally thousands, maybe tens of thousands of directions over months”, Otto says.No two chronic infections are identical. But in dozens of case reports, researchers have begun to identify common signatures of long-term infection.