A lack of testing data and government guidance led many to avoid the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy.

Late one afternoon last October, Dr. Shelley Odronic sat in her office and, just as she had thousands of times before, slid a rectangular glass slide onto her microscope.

Heerema-McKenney was in her office when the phone rang. As she listened, she knew that what Odronic was describing was what she and her colleagues had observed repeatedly over the past several months: a patient positive for the coronavirus, a placenta destroyed by COVID-19, a baby stillborn. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contributed to the confusion with vague early messaging about whether pregnant people should get vaccinated. While Americans lined up at pharmacies and stalked vaccine websites in hopes of securing a shot last year, pregnant people had some of the lowest vaccination rates among adults, with only 35% fully vaccinated by last November.

COVID-19 also led to stillbirths among pregnant people who became exceedingly ill after contracting the virus. It damaged their lungs and clotted their blood, putting their babies in such severe distress that they were born before they could take their first breath.She and others had tried to alert the CDC as well as maternal and state health organizations to their findings, but she said they either didn’t get a response or were told they needed to collect more data and publish studies.

The pandemic had already brought much change to their lives. Ginger, who lives in the small town of Washington Court House in southwest Ohio, quit her job as assistant nutrition director with the county’s Commission on Aging. She stationed hand sanitizer throughout her house and in her car, and she only went grocery shopping early in the morning. If she noticed someone in an aisle, she skipped it.

At a backyard gender reveal three months later, Ginger’s growing belly resembled a basketball against her tiny frame. She leaned in to kiss her husband, her long, dark hair falling onto her shoulders. Red confetti rained down on the deck. “You were so scared,” Kendal wrote in a notebook that night. “We told each other over and over how much we loved each other.”

The plan, records show, was to deliver at 28 weeks. But the day after Ginger was put back on life support, Kendal got the call telling him the baby was on her way. As doctors prepared for the delivery in Ginger’s intensive care room, the family camped out in the waiting room, jittery from excitement and vending machine snacks. They talked about baby names and future family outings.

When Ginger woke up, she looked down at her sunken belly and realized she had given birth. She assumed her daughter was in the newborn intensive care unit. Ginger was barely able to speak around the tube in her trachea, but after a few days in which no one brought the baby to her, she couldn’t wait any longer. Ginger turned to her mother and sister and mouthed the words, “Where’s the baby?”

Shortly before leaving office, President Barack Obama signed into law the 21st Century Cures Act, which established the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women. The group found longstanding obstacles, including liability concerns, to including pregnant and lactating people in clinical research.

“We were frustrated because COVID-19 provided an opportunity to implement the recommendations of the task force,” said Dr. Diana Bianchi, the director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the chair of the task force. Some government officials, including several from the Food and Drug Administration, said they support having pregnant women take part in clinical studies of vaccines for emerging infectious disease, including COVID-19. A spokesperson for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, said the agency did not “dictate the protocol development” for the trials and said that responsibility lies with the companies.

A dizzying and vague series of advisories led to confusion and delayed vaccinations. When the COVID-19 vaccines were first made available in December 2020, the CDC said health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities should be prioritized, but the shots were not explicitly recommended for pregnant people. Instead, the agency said on its webpage for vaccines and pregnancy that pregnant health care workers “may choose to be vaccinated.

Once again, pregnant people were put in the precarious position of receiving ambiguous and inconsistent recommendations. In May 2021, the CDC reiterated that pregnant people faced an increased risk of getting severely ill from COVID-19, but the language surrounding the vaccine — “If you are pregnant, you can receive a COVID-19 vaccine” — was noncommittal.

In the beginning, she said, the only pregnancy-specific data they had came from a few dozen participants who were inadvertently included after becoming pregnant during the clinical trials and from some pregnant animal data. “The vaccines are safe and effective,” Walensky said in a statement at the time, “and it has never been more urgent to increase vaccinations as we face the highly transmissible Delta variant and see severe outcomes from COVID-19 among unvaccinated pregnant people.”

A separate CDC database shows more than 220,000 COVID-19 cases and at least 305 deaths among pregnant people. “I kept seeing it happening more and more to women and it wasn’t talked about,” she said. “They just say, ‘Oh, get the vaccine,’ which is great, but they don’t talk about what getting the virus can do to pregnant women.”

They were taking precautions, Butcher said, especially since the vaccine wasn’t yet available to her or her husband. But a week later, she woke up with a runny nose, though she didn’t think much of it. Still, she went to the hospital to make sure everything was OK. An ultrasound came back normal. “I was in shock. I was in shock that I lost my daughter, in shock that I had COVID,” Butcher said. “She should be alive, but it’s because of COVID that I lost her.”

Butcher, now 45, scheduled her vaccine as soon as she could. Her second dose fell on what was supposed to be Emily’s due date. After getting the shot, she and her husband drove up to Cleveland to visit their daughter’s grave and tell her that her mother got the vaccine in her honor. They let her know how much she was loved and how desperately they wished she was still safe inside her mother’s womb.

While 71% of pregnant people were fully vaccinated as of mid-July, a figure not much lower than national vaccination rates for people 18 or older, only around 2% received at least one of their shots while they were pregnant — suggesting that persuading people who are already pregnant to get vaccinated remains a challenge. Research points to afive to eight months after getting the first vaccine, yet only 58% of pregnant people were boosted.

Indonesia Berita Terbaru, Indonesia Berita utama

Similar News:Anda juga dapat membaca berita serupa dengan ini yang kami kumpulkan dari sumber berita lain.

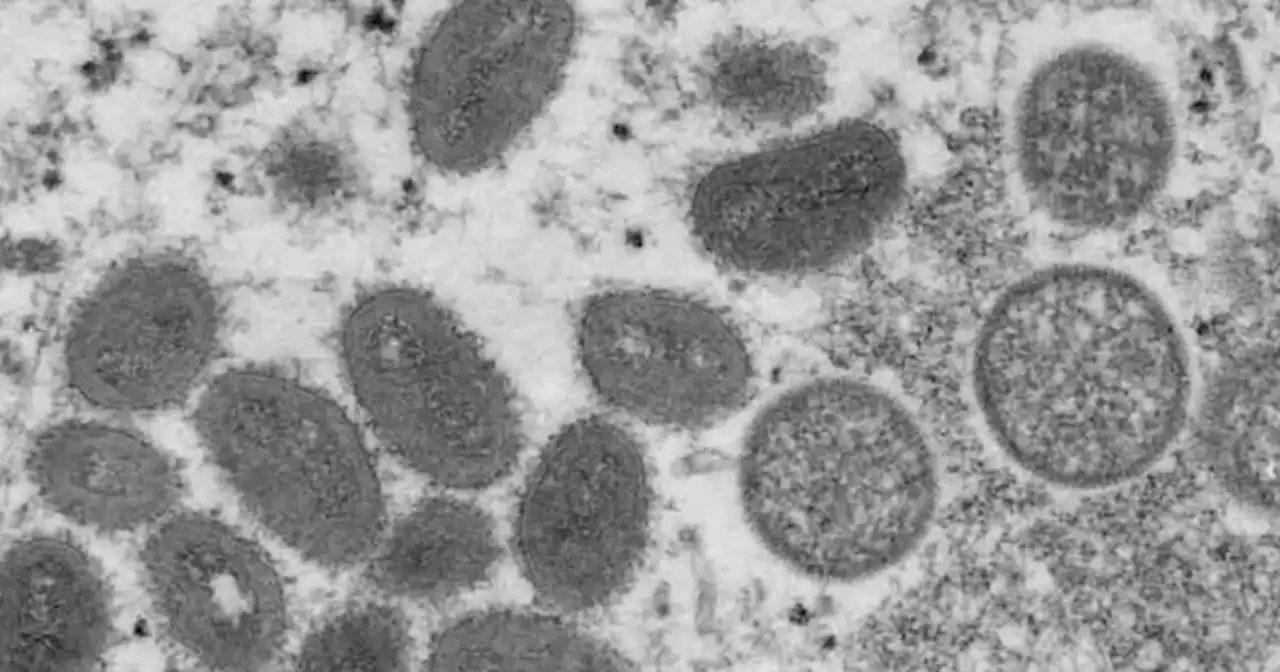

Monkeypox is less deadly and contagious than COVID-19, and there is a vaccineThe Annenberg Center for Public Policy surveyed Americans and found 48% weren't sure if monkeypox was less contagious than COVID-19. It is, because it’s only transmitted through close contact.

Monkeypox is less deadly and contagious than COVID-19, and there is a vaccineThe Annenberg Center for Public Policy surveyed Americans and found 48% weren't sure if monkeypox was less contagious than COVID-19. It is, because it’s only transmitted through close contact.

Baca lebih lajut »

Harris County Public Health now administering COVID-19 Novavax vaccineAre you planning on getting vaccinated against COVID-19? You now have a new vaccine to choose from.

Harris County Public Health now administering COVID-19 Novavax vaccineAre you planning on getting vaccinated against COVID-19? You now have a new vaccine to choose from.

Baca lebih lajut »

Novavax's COVID vaccine rollout off to sluggish start with just 7,000 dosesLast month, officials from the CDC signed off on use of Novavax's COVID-19 vaccine for those 18 years and older.

Novavax's COVID vaccine rollout off to sluggish start with just 7,000 dosesLast month, officials from the CDC signed off on use of Novavax's COVID-19 vaccine for those 18 years and older.

Baca lebih lajut »

Novavax's COVID vaccine rollout off to sluggish start with just 7,000 dosesLast month, officials from the CDC signed off on use of Novavax's COVID-19 vaccine for those 18 years and older.

Novavax's COVID vaccine rollout off to sluggish start with just 7,000 dosesLast month, officials from the CDC signed off on use of Novavax's COVID-19 vaccine for those 18 years and older.

Baca lebih lajut »

Senate Democrats avoid COVID-19 testing ahead of key voteSenate Democrats reportedly have an unspoken agreement to avoid testing for COVID-19 because their hopes of passing the Inflation Reduction Act depend on all 50 members being present in the chamber in the days ahead.

Senate Democrats avoid COVID-19 testing ahead of key voteSenate Democrats reportedly have an unspoken agreement to avoid testing for COVID-19 because their hopes of passing the Inflation Reduction Act depend on all 50 members being present in the chamber in the days ahead.

Baca lebih lajut »

‘COVID bunny rabbits’ being returned, overwhelming rescue groups and some sheltersPeople are returning ‘COVID bunnies’ in SoCal, filling some shelters, as rescue groups cope with a domestic rabbit population explosion.

‘COVID bunny rabbits’ being returned, overwhelming rescue groups and some sheltersPeople are returning ‘COVID bunnies’ in SoCal, filling some shelters, as rescue groups cope with a domestic rabbit population explosion.

Baca lebih lajut »